Today in Science History - Quickie Quiz

Today in Science History - Quickie Quiz

Alexander George McAdie

American meteorologist who followed Benjamin Franklin in employing kites in the exploration of high altitude air conditions. He was second director of the Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory.

By ALEXANDER McADIE.

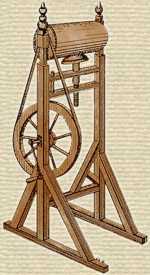

Franklin's Electrical Machine.Colorization © todayinsci (Terms of Use)

Thank you.

For offline use, click Terms of Use tab on top menu.

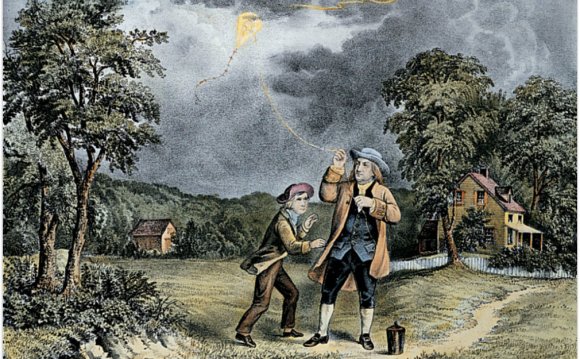

[p.739] THE recent improvements in kites have suggested perhaps to many the question, “How would Franklin perform his kite experiment to-day?” It may seem a little presumptuous to speak for that unique philosopher, and attempt to outline the modifications he would introduce were he to walk on earth again and fly kites as of yore; for, with the exception of Jefferson, perhaps his was the most far-seeing and ingenious mind of a remarkable age. But the world moves; and in making kites, as well as in devising electrometers and apparatus for measuring the electricity of the air, great advances have been made. Franklin would enjoy repeating his kite experiment to-day, using modern apparatus. What changes and lines of investigation he would suggest are beyond conjecture.

A hundred and fifty years ago a ragged colonial regiment drew up before the home of its philosopher-colonel and fired an ill-timed salute in his honor. A fragile electrical instrument was shaken from a shelf and shattered. Franklin doubtless appreciated the salute and regretted the accident. In the course of his long life he received other salutes, as when the French Academy [p.740] rose at his entrance; and he constructed and worked with other electrometers; but for us that first experience will always possess a peculiar interest. The kite and the electrometer betray the intention of the colonial scientist to explore the free air, and, reaching out from earth, study air electrification in situ. He made the beginning by identifying the lightning flash with the electricity developed by the frictional machine of that time. A hundred patient philosophers have carried on the work, improving methods and apparatus, until to-day we stand upon the threshold of a great electrical survey of the atmosphere. It is no idle prophecy to say that the twentieth century will witness wonderful achievements in measuring the potential of the lightning flash, in demonstrating the nature of the aurora, and in utilizing the electrical energy of the cloud. The improved kite and air-runner will be the agency through which these results will be accomplished.

The famous kite experiment is described by Franklin in a letter dated October 19, 1752: “Make a small cross of light sticks of cedar, the arms so long as to reach to the four corners of a large, thin silk handkerchief when extended. Tie the corners of the handkerchief to the extremities of the cross, so you have the body of a kite which, being properly accommodated with a tail, loop, and string, will rise in the air like those made of paper, but being made of silk is better fitted to bear the wet and wind of a thunder gust without tearing. To the top of the upright stick of the cross is to be fixed a very sharp-pointed wire rising a foot or more above the wood. To the end of the twine next the hand is to be tied a silk ribbon, and where the silk and twine join a key may be fastened. This kite is to be raised when a thunder gust appears to be coming on, and the person who holds the string must stand within a door or window, or under some cover, so that the silk ribbon may not be wet; and care must be taken that the twine does not touch the frame of the door or window. As soon as the thunder clouds come over the kite, the pointed wire will draw the electric fire from them, and the kite, with all the twine, will be electrified, and stand out every way and be attracted by an approaching finger. And when the rain has wet the kite and twine you will find the electric fire stream out plentifully from the key on the approach of your knuckle.”

The famous kite experiment is described by Franklin in a letter dated October 19, 1752: “Make a small cross of light sticks of cedar, the arms so long as to reach to the four corners of a large, thin silk handkerchief when extended. Tie the corners of the handkerchief to the extremities of the cross, so you have the body of a kite which, being properly accommodated with a tail, loop, and string, will rise in the air like those made of paper, but being made of silk is better fitted to bear the wet and wind of a thunder gust without tearing. To the top of the upright stick of the cross is to be fixed a very sharp-pointed wire rising a foot or more above the wood. To the end of the twine next the hand is to be tied a silk ribbon, and where the silk and twine join a key may be fastened. This kite is to be raised when a thunder gust appears to be coming on, and the person who holds the string must stand within a door or window, or under some cover, so that the silk ribbon may not be wet; and care must be taken that the twine does not touch the frame of the door or window. As soon as the thunder clouds come over the kite, the pointed wire will draw the electric fire from them, and the kite, with all the twine, will be electrified, and stand out every way and be attracted by an approaching finger. And when the rain has wet the kite and twine you will find the electric fire stream out plentifully from the key on the approach of your knuckle.”

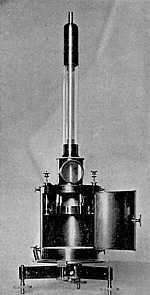

Mascart Electrometer.

[p.741] Now, how would we perform this experiment to-day and with what results? Having flown big kites during thunderstorms, it may perhaps be best to describe step by step two of these experiments, and then speak of what we know can be done, but as yet has not been done.

Our first repetition of Franklin's kite experiment was at Blue Hill Observatory, some ten miles southwest of Boston, one hundred and thirty-three years after its first trial. There were two large kites silk-covered and tin-foiled on the front face. These kites were of the ordinary hexagonal shape, for in 1885 Malay and Hargrave kites were all unknown to us. Fifteen hundred feet of strong hemp fish line were wrapped loosely with uncovered copper wire of the smallest diameter suitable, and this was brought into a window on the east side of the observatory, through rubber tubing and blocks of paraffin. Pieces of thoroughly clean plate glass were also used. Materials capable of giving a high insulation were not so easily had then as now. We knew very little about mica; and quartz fibers and Mascart insulators could not be obtained in the United States. Our electrometer, however, was a great improvement upon any previous type, and far removed from the simple pith-ball device used by Franklin.

Knowing that an electrified body free to move between two other electrified bodies will always move from the higher to the lower potential, Lord Kelvin devised an instrument consisting of four metallic sections, symmetrically grouped around a common center and inclosing a flat free-swinging piece of aluminum called a needle. The end of the kite wire is connected with the needle and the sections or quadrants are alternately connected and then electrified, one set with a high positive potential, say five hundred volts, and the other with a corresponding negative value, say five hundred volts lower than the ground.

Mascart Electrometer, with Photographic Register, July, 1892.

Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory.

Electrical Potential of the Air.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE